Black Holes¶

Glossaries

- ZAMO: zero angular-momentum observer

Observations of Black Holes¶

LIGO!

There are several ways of detecting black holes, directly or indirectly.

- Gravitational effects: such as lensing, binary systems, gravitational waves.

- Matter around it: orbit of stars around black holes, emission of accretion discs, final stage of Hawking radition.

Several astronomical tips:

- As for accretions, pulsars are steady because of the magnetic field they are holding. Black holes do not hold magnetic field like that so it can not be a steady pulsation.

- There is a star orbiting the center of our galaxy at an orbit of 120AU, which helps us determing the mass of the center object.

- First generatioin of stars (population III stars) might form supermassive black holes, and might still be around since Hawking radiation of massive black holes is low.

- Black hole collisions are studied using computers numerically. Such simulations have intrinsic instability due to the fact that GR has coordinate freedom and singularities.

- Simulations found kicks of black holes. Black hole mergers starting with asymmetries will develop asymmetric emission of gravitational waves thus kicking the system in the opposite direction.

Schwarzschild Metric¶

The line element for Schwarzschild metric is

The inverse of metric elements \(g^{\alpha\beta}\) are easily obtained since the metric is diagonal in this basis.

Kerr Metric¶

To begin with, Kerr spacetime around a Kerr black hole of mass \(M\), spin angular momentum \(J\), is described as the line element

where

The Kerr metric has very nice symmetries.

- Reflection symmetry with respect to \(\theta=\pi/2\);

- Axial symmetry around the \(z\) axis so that the angular momentum \(L_\phi=p_\phi\) is conserved;

- Stationary metric so that energy of test particles is conserved, \(E = -p_0\) is conserved.

Frame Dragging¶

We would be very interested in how the rotation of black holes drag the spacetime. Due to the symmetries, the equatorial plane is easier to think about. So we set \(\theta=\pi/2\). For frame dragging, we have a guy riding a rocket so that \(p_r=0\). The frame dragging is best described by a observor that is staying stationary with frame, that is a zero angular momentum observor (ZAMO), that \(p_\phi=0\). Frame dragging angular velocity is

It can be derived that the frame dragging angular velocity at radius \(r\) is

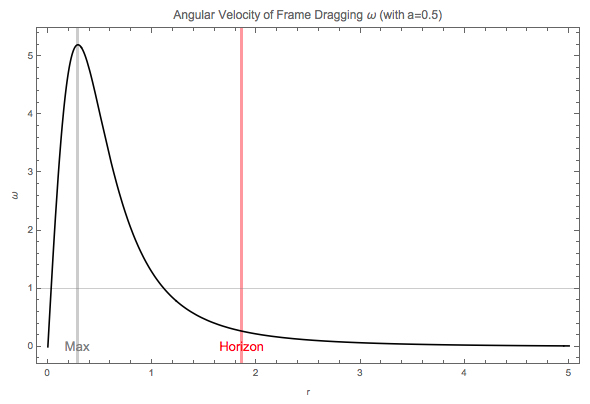

Fig. 25 Angular velocity of the frame dragging for a Kerr black hole. Everything is scaled by the mass of black hole. It drops as \(1/r^3\) for large \(r\).

Mathematica (11) Code for the Plot

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | In[1]:= omega[r_,a_:0.2,mass_:1,theta_:0]:=Module[{deltaM},

deltaM=r^2-2mass r+a^2;

2mass r/( (r^2+a^2)^2-a^2 deltaM Sin[theta]^2 )

]

In[2]:= Solve[D[omega[r,a],r]==0,r]

Out[2]= {{r->-(a/Sqrt[3])},{r->a/Sqrt[3]}}

In[3]:= Manipulate[

Plot[omega[r,a],{r,0,5},

Frame->True,FrameLabel->{"r","\[Omega]"},

ImageSize->Large,PlotRange->Full,PlotStyle->Black,

GridLines->{{ {a/Sqrt[3],

Directive[Gray,Thick]},{1+Sqrt[1-a^2],Directive[Red,Thick]}},{1}},

Epilog->{Inset[Style["Horizon",13,Red],{(1+Sqrt[1-a^2]),0},{0,0}],

Inset[Style["Max",13,Gray],{a/Sqrt[3],0},{0,0}]},

PlotLabel->"Angular Velocity of Frame Dragging \[Omega] (with a="<>ToString@a<>")"],

{{a,0.5,"Spin Angular Momentum of Black Hole"},0,1}

]

|

Ergospheres, Horizons¶

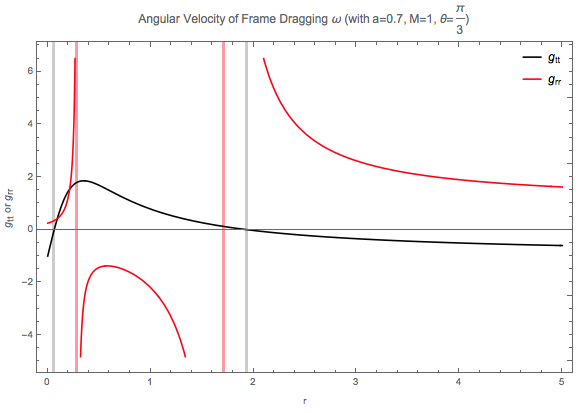

In Schwarzschild black holes, the surface that \(g_{tt}=0\) and \(g_{rr}\to\infty\) are the same surface that is defined as the horizon. However, \(g_{tt}=0\) gives us the ergospheres and \(g_{rr}\to\infty\) gives us the horizons.

Why?

The ergospheres are the regions that even light can not travel in the counter-rotation direction. That being said, \(p^\phi\) can only be positive for light. To prove this, we set \(ds^2=0\) and neglect \(p_r\),

which shows that,

We can show that \(p^\phi\) can only be negative if \(g_{tt}>0\), while it can be negative or positive if \(g_{tt}<0\). What we found is that for \(g_{tt}>0\), we are entering a region where even light can not travel against the direction of the rotation. This is why we define the condition \(g_{tt}=0\) to be the surface of the ergospheres.

As for \(g_{rr}\to\infty\), it is the condition for \(p^r\) being always negative, which means we are always travelling inward. It proven by similar techniques.

We have two ergospheres and horizons! Solving \(g_{tt}=0\) gives us

which defines the two surfaces of ergospheres.

Meanwhile, \(g_{rr}\to\infty\) indicates that \(\Delta=0\), which proves to be

which shows us the two horizons.

Fig. 26 \(g_{tt}\) and \(g_{rr}\) as function of coordinate \(r\).

Mathematica (11) Code

gtt[r_,a_,mass_:1,theta_:Pi/2]:=Module[{deltaM,rhosquareM},

deltaM=r^2-2mass r+a^2;

rhosquareM=r^2+a^2Cos[theta]^2;

-(deltaM-a^2Sin[theta]^2)/rhosquareM

]

grr[r_,a_,mass_:1,theta_:Pi/2]:=Module[{deltaM,rhosquareM},

deltaM=r^2-2mass r+a^2;

rhosquareM=r^2+a^2Cos[theta]^2;

rhosquareM/deltaM

]

Manipulate[

Plot[{gtt[r,a,mass,theta],grr[r,a,mass,theta]},{r,0,5},Frame->True,FrameLabel->{"r","Subscript[g, tt] or Subscript[g, rr]"},ImageSize->Large,PlotRange->Automatic,PlotStyle->{Black,Red},GridLines->{{ {mass+Sqrt[mass^2-a^2],Directive[Red,Thick]},{mass+Sqrt[mass^2-a^2Cos[theta]^2],Directive[Gray,Thick]},{mass-Sqrt[mass^2-a^2],Directive[Red,Thick]},{mass-Sqrt[mass^2-a^2Cos[theta]^2],Directive[Gray,Thick]}},None},PlotLabel->"Angular Velocity of Frame Dragging \[Omega] (with a="<>ToString@a<>", M="<>ToString@mass<>", \[Theta]="<>ToString@TraditionalForm@theta<>")",PlotLegends->Placed[{"Subscript[g, tt]","Subscript[g, rr]"},{Right,Top}]],

{{a,0.7,"Spin Angular Momentum of Black Hole"},0,1},{{mass,1,"Mass of Black Hole"},0.1,10},{{theta,Pi/3,"\[Theta]"},0,Pi}

]

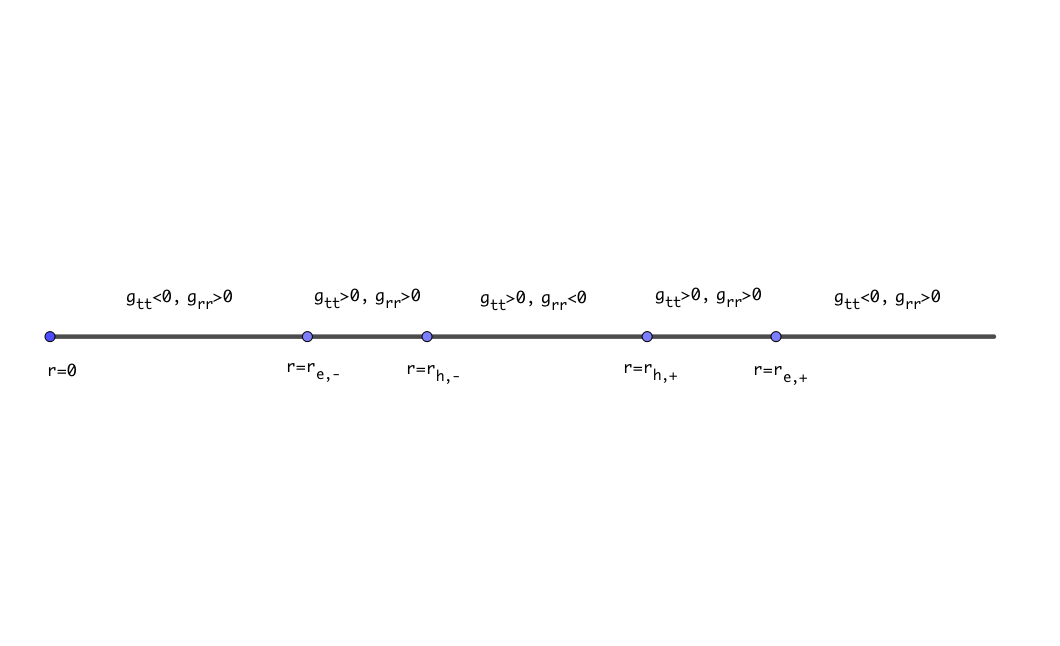

In fact we can prove that

- Within region \(r>r_{e,+}\), \(g_{tt}<0\), \(g_{rr}>0\);

- Within region \(r_{h,+}<r<r_{e,+}\), \(g_{tt}>0\), \(g_{rr}>0\);

- Within region \(r_{h,-}<r<r_{h,+}\), \(g_{tt}<0\), \(g_{rr}<0\);

- Within region \(r_{e,-}<r<r_{h,-}\), \(g_{tt}<0\), \(g_{rr}>0\);

- Within region \(r<r_{e,-}\), \(g_{tt}<0\), \(g_{rr}>0\).

Fig. 27 Regions of Kerr black holes. \(r_{e,\pm}\) are the two surfaces of ergospheres, \(r_{h,\pm}\) are the two horizons, as calculated previously.

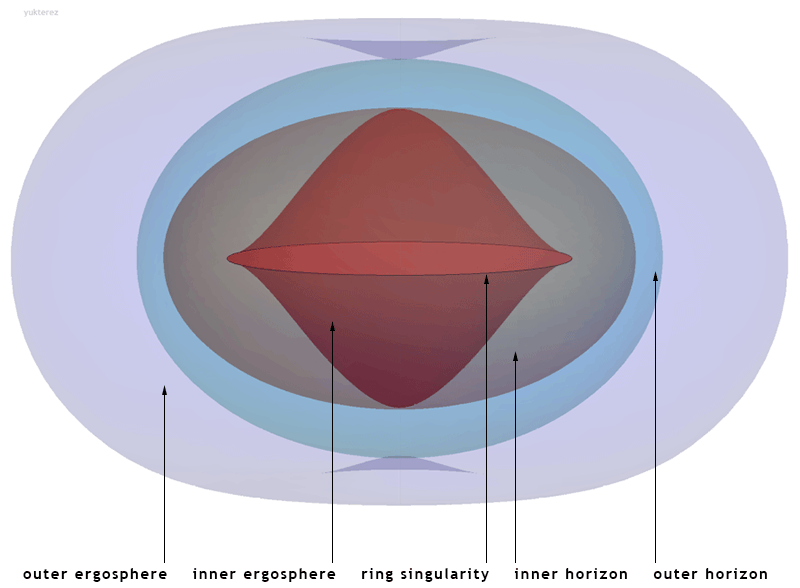

Fig. 28 A Kerr black hole is nicely visualized by Simon Tyran, whose work is licensed with CC BY-SA.

What are the significances of the surfaces?

For the outer horizon and outer ergosphere, their properties are discussed. What are the properties of the inner surfaces?

Photons Travelling on Equatorial Plane¶

The elements of the metric \(g_{\alpha\beta}\) as well as \(g^{\alpha\beta}\) are frequently used. It is essential to find them, which involves some matrix inversion.

Inverse of Block Diagonal Matrix

For a given matrix

the inverse of it \(A^{-1}\) is

This result works for arbitrary dimensions.

Inverse of 2 by 2 Matrix

For a 2 by 2 matrix

the inverse is

Penrose Process¶

Suppose we have a particle falling inside a black hole, starting with 0 energy at infty. It falls through the ergosphere, and decays into two particles, A and B. Particle A obtains a negative energy, meanwhile having negative angular momentum, so that it stays in ergosphere or falls through the horizon. The other particle obtains positive energy, and managed to escape. Energy conservation tells us that the escaped particle will have energy at infty that is larger than the initial energy 0.

This though experiment relies on the effective potential \(V(r)\) of the ergosphere. For positive angular momentum, we always fall through the